THE LOG is a periodical series about daily encounters giving inspirations for thinking and writing.

“THE LOG” 的中文版本为 近处 .

Tibetan Green Tara, China's Dynasties & The End of History?

Green Tara, by Karsang Lama, Tibet House, New York, 2017

Out of the sheer fear that one day I will lose memory of the great places I visited, the great people I met, and the great readings inspired my thinking in the past 10 days, I’m keeping this LOG: it starts from April 14, the Good Friday when I had the chance to visit the Tibet House for a Tibetan Tangka exhibition by Karsang Lama, a Nepali Tangka master who I met in person at China Institute in March, and ends on April 22, when I was inspired by reading Francis Fukuyama’s 1989 monograph, “The End of History?”, while sipping a glass of red wine in my apartment in Astoria, Queens. These two seemingly drastically unrelated activities, in the end, are also very closely connected, as I will explain in this LOG.

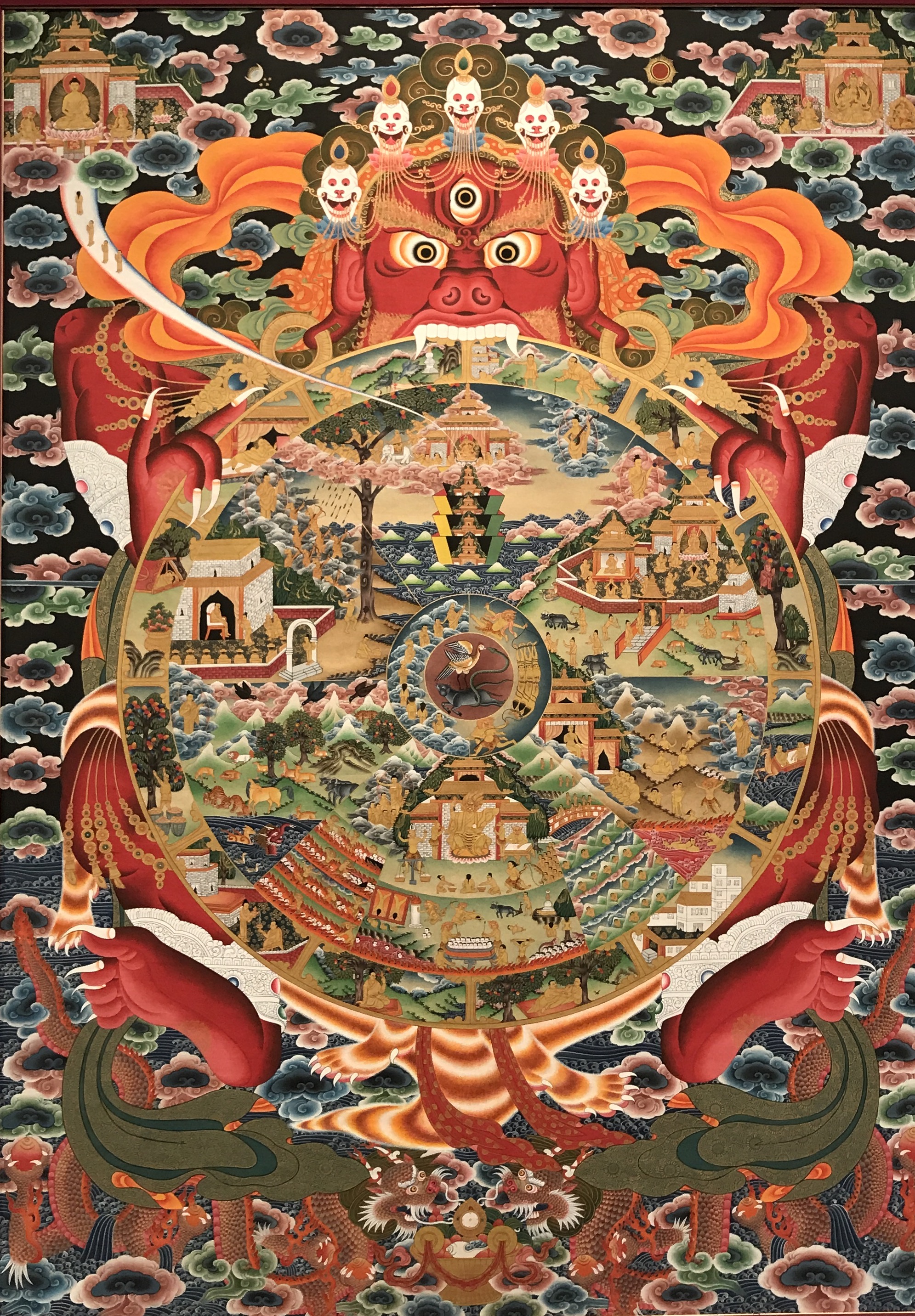

The Tibet House is located very nicely on 15th Street between 5th and 6th Avenue in Manhattan, only a few blocks from the magnificent Rubin Museum of Art. However, its entrance is not hard to miss. I first walked in the hotel sharing the same address and was told the real entrance was next door. Nevertheless, the Tibetan Tangka exhibition was fantastic. Tangka, a Tibetan Buddhism art form with a mesmerizing meticulous style, paints on silk or canvas of Buddhist deities, scene, or mandala (Xue, 2016) in natural mineral pigment of bright colors. My favorite one is the Green Tara (Syamatara in Sanskrit), undoubtedly because of the astonishing artistic representation of this graceful, elegant goddess, and partially because I took the time to learn about Green Tara as “the mother of all Buddha and savior of all sentient beings from worldly miseries” (quote from the exhibit handbook). It was the first time I ever walked into the Tibet House, which might indicate my sub-consciousness of the fact that Dalai Lama is the top patron of this cultural-political organization. Nevertheless, I was extremely happy when browsing through the amazing Tangka masterworks. Admission free, I was for a while the only viewer there. A couple of staff talked loudly while adjusting a computer for an event later in the exhibition room, where in the middle a number of chairs were set, surrounded by beautiful Buddhas, Tara, Deities, the Wheel of Life, etc.

the Wheel of Life, by Karsang Lama, Tibet House, New York 2017

Since I didn’t have to look for decorated Easter Eggs this weekend, I decided to make this weekend even more culturally enriched by spending the next day visiting the Ages of Empires, a new exhibition at the MET opened in early April. Ages of Empires is about the Qin and Han Dynasties, allegedly the “classical period” of China, extremely important in shaping the “Chinese identity” during a time roughly equivalent to the Greco-Roman period in western civilization. The exhibition of 160 objects included a few Terracotta soldiers of the first Emperor of China, Qin Shihuangdi (259 – 210 B.C.), and a well-preserved jade suite of Dou Wan, the wife of Prince Liu Sheng in Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – A.D. 9). This MET blockbuster exhibition captures apparently not only the imagination of the non-Chinese, but also many Chinese who happen to be in NYC (including me!). In fact, on this Saturday afternoon, I would say about two-thirds viewers in the packed gallery were Chinese. For someone working at China Institute, which brings to NYC another jade suite in a couple of months, I found it’s highly impressive that the MET managed to bring these 160 objects from over 20 museums in China. Imagine the bureaucracy of such operation to assemble the pieces together as they are now in the MET gallery on 5th Avenue: each piece, probably the most valuable treasure by the individual Chinese museum (otherwise what’s the point of showing at the MET?) , requires careful and quite often time-consuming negotiations in order to be moved from its home in China and placed in its exact final representation here at the MET. As I’m hosting a professional development workshop on the Han Dynasty for a group of K-12 Chinese language teachers in a week, a visit to Ages of Empires seemed a must-to-do homework – the Chinese national treasures normally thousands of miles away and all over the country were now in one place and only a few subway stops away.

As if the weekend was not intellectually stimulating enough, in the following Thursday evening at China Institute, there was a screening of a Chinese documentary film about craftsmen restoring antiquities collected by emperors of Qing Dynasty (1644 - 1912), Masters in the Forbidden City, which surprisingly went viral in China since released in 2016. Prof. Lei Jianjun, producer of the film and a faculty at the renowned Tsinghua University in journalism and communication, would be there for Q&A. I decided to attend the event though was torn as Thursday was my PRECIOUS weekly badminton night at the nearby Stuyvesant Community Center. Mid-height with a solid build, Prof. Lei’s subdued yet eloquent style was well received by the audience. So was the Q&A moderator, Dr. Ming Xue from the Museum of Natural History. As it turned out, Prof. Lei and I both were alumni of Beijing Normal University and even shared common acquaintance(s), in addition to Prof. Yibing Huang (also well known as a contemporary poet with a pen name as 麦芒 Mai Mang), who introduced Prof. Lei and the film to China Institute. At one point, Prof. Lei pointed out the unusual popularity of the documentary in China while the majority of Chinese documentaries struggled to appeal to a large, young audience. At the very least, the simple and caring relationship between the craftsmen and the precious antiquities in the Forbidden City where Chinese emperors resided seems so authentic and rare in today’s China where ideological void has become an increasing concern, especially for the young generation all too familiar with the overwhelming consumerism. Such authenticity offers an opportunity to discover an alternative meaning between people and materials, to the point that it’s almost spiritual, if not religious. Not surprisingly, as the documentary catching fire in China, the Forbidden City Cultural Relic Restoration Department received overwhelming job applications the following year, a pleasant turning point to build the pipeline for a future generation of craftsmanship.

Finally on Friday evening of April 21, the workshop I was in charge for Chinese language teachers, Han Dynasty in China and World History, started and ended as planned. Prof. Yu Renqiu, Senior Lecturer of China Institute and Professor of history at SUNY Purchase College, gave a brilliant lecture on Han Dynasty (and Qin) for about 1.5 hours. A well respected historian on China and U.S. with a charismatic scholarly appearance, Prof. Yu highlighted the importance of the unification in Qin Dynasty, and managed to cover such details in one and half hours of Han Dynasty including its rather complicated 400-year history, its advanced political system, the establishment of the state doctrine of Confucianism and the its great significance in shaping China’s 2,000 years of imperial history. As a historian, Prof. Yu's face was lit up when introducing the great historian Si Maqian (145 or 135 – 86 B.C.) , who technically was the very first great historian of China who produced the Grand Record of Historian. Apparently after thousands of years in New York, there was still a sense of instant connection shared among historians.

It is because of Prof. Yu’s lecture, quoting Francis Fukuyama to point out the brilliant political system of Han Dynasty virtually fulfilling Max Weber’s classic definition of modern bureaucracy, I found myself reading Fukuyama’s 1989 monograph, The End of History?, the night of Saturday. A renowned professor writing widely on democracy, development and international politics, Fukuyama’s 1992 book, The End of History and the Last Man, which has appeared in over 20 foreign editions, was an extension of this monograph, in which, Fukuyama claimed the “end of history”:

“The end of history will be a very sad time. The struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one’s life for a purely abstract goal, the worldwide ideological struggle that called for the caring, courage, imagination and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands. In the post historical period there will be neither art nor philosophy, but the perpetual care taking of the museum of human history.”

Of course, human activities will continue along an irreversible moving timeline. And history books will always add new chapters as events unfolding, just like headlines (and much much more of them nowadays than ever!) appear on daily newspapers and social media outlets. By claiming “the end of History”, Fukuyama essentially argues liberal democracy as the “final form of human government”, which as an ideal has nowhere to progress towards. In the world of 1989, it seemed western liberal democracy has secured as the ultimate ideological form for all human societies, with Fascism effectively destroyed after WWII, and Communism diminished to an unthreatening position in both Soviet Union and China. Yet, this ultimate triumph is unlikely leading to a forever-happy ending: While I am not entirely convinced that liberal democracy is the end of the History, I share the pessimism that the sense of meaningfulness produced by the very ideological struggle will cease to exist, ironically, as soon as the triumph is achieved.

Neither an historian nor a political science scholar, I may not have liberal democracy often in my vocabulary. However, the omniscient media reports of the recent political dramas in U.S., Europe and Asia forcefully make me think, or even feel, liberal democracy (like the evening of Nov. 9, 2016 when Trump won the U.S. Presidency) on a daily basis, not in a way that it has reached its final ideal form, but all the flaws it could carry in reality. On the other hand, it’s awfully accurate that without the imagination of certain idealism, societies as a whole could run like a headless chicken: issues on economy, technology, environment are all very important, however none could offer an ideological core for all to center around. Reading Fukuyama, I couldn’t help but to reflect on my own very trivial life activities in this past 10 days. While each seemed to be incredibly rich in content, at least in cultural sense, it is hard to connect those individual events in a narrative that would make sense in a bigger picture. Once the excitement at the moment fades, the void of a core is felt immediately. Ironically, speaking of “sophisticated consumerism”, I just booked a ticket to Vancouver in search for a yoga retreat…

It’s not new that human life, whether taken individually or collectively, is said to resemble an endless flow of meaningless events (e.g. Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time). Maybe such sense is inescapable for anyone and everyone. And yet life must go on, and as a sentient being we all need to endure such misery. Thus I’m seeking the comfort in the arts and culture conveniently available in NYC (special thanks to Green Tara) and the writing of them, during which I enjoyed the tranquility and satisfaction the craftsmen may feel in the Forbidden City. The only difference is, sadly, my comfort is only momentary.

Rhinoceros, Han-dynasty China (206 B.C. - A.D. 220), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2017

April 24, 2017

Astoria, New York

_____________________

Ming Xue, "The Rise of the Individual through Tibetan Thangka Painting", CUNY Forum, 2016.