by Shenzhan/申展

A literati salon has a long tradition in China. I tend to also associate a Chinese literati salon with the ancient Greek symposium, an intellectual gathering with music and wine, which sounds so much more interesting than its contemporary version.

The original story of the Chinese literati salon started in the spring of 353 A.D., when Wang Xizhi (王羲之), the greatest calligrapher, gathered a group of his friends, i.e., cultural and social elites including notable scholars, artists, officials, etc. at the Orchid Pavilion, a place surrounded by nature, along a winding stream. At the gathering, the men (yes, all of them were men) were playing a game - cups with wine were placed in the stream and floated among the guests who were sitting along the stream. Whoever picked up the wine had to come up with a poem. In the end, there were over 20 poems written. Wang Xizhi, on the spot, wrote the Preface to the Orchid Pavilion (《兰亭集序》) in calligraphy for the poem collection. Today, almost no one remembers the poems, but everyone with the slightest knowledge of Chinese calligraphy would know about the Preface as the most celebrated calligraphy piece in China’s history. The gathering, known as the Orchid Pavilion Gathering, became the very origin of Chinese literati salon, also called Elegant Gathering (雅集),which typically involves a variety of elegant art forms including calligraphy, brush painting, poetry, possibly music, and definitely wine. The gathering itself has been reimagined and represented in calligraphy, brush paintings, poems, etc. for over 1,700 years afterwards. Many tried to replicate such a gathering, even in the year of 2021 in New York.

The circumstance was quite unusual on Friday, December 17, 2021, in New York. It was the second winter of the covid19 pandemic. After a few months of slight relief when many people felt to see the end of the tunnel after two shots of vaccinations, a new variant, Omicron, was at the verge of sweeping through the city, U.S. and the world. The gathering, named China Institute Literati Salon: Along the Hudson River, was planned weeks ago without the slightest knowledge of omicron, nor the prediction of what it was to become. Over 50 guests were expected to show up.

At 6: 00 pm, people, either clueless of the omicron, or voluntarily taking the risk regardless, started coming to the large multifunction hall on the 2nd floor of China Institute in lower Manhattan. The hall was set up with desks six feet apart with calligraphy paper, ink and brushes for two, surrounding in the center an “L” shape stage where 3 musicians were playing pipa, flute and percussion. A calligrapher was sitting across from the stage writing calligraphy. A minimalist podium was placed in between the stage and the calligraphy desk. The podium was for me.

As the hostess and creator of the program, I was pleased to see things unfolding as planned: artists were in place (they have been, in fact, rehearsing since the morning); guests were walking around and finding their places to settle down; technology seemed to work so far. The hall, with over 20 desks, was getting full. One desk suddenly collapsed, ink splashed on the floor, and a guest’s winter jacket. Thank GOD my colleagues were there to reset everything quickly while waving to me, “Go start the program! “And the tinted winter jacket was black, the same color as the ink!

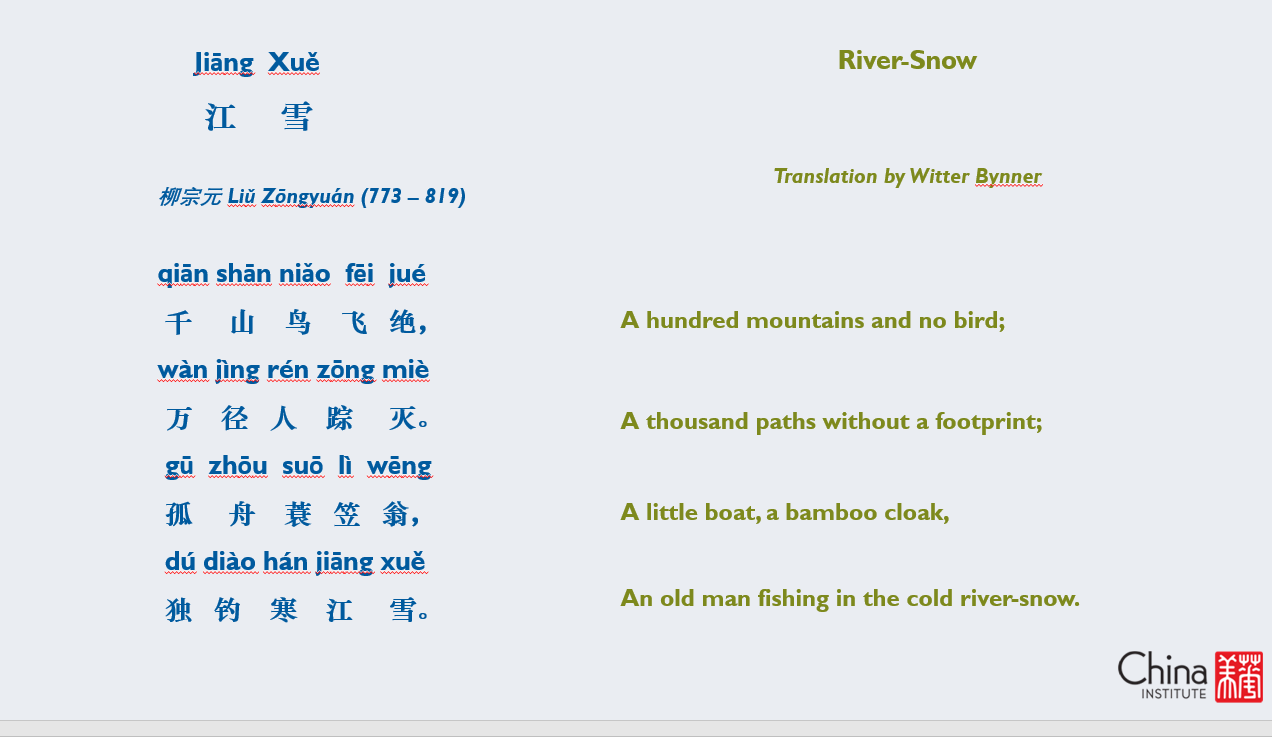

The program officially started at 6: 30pm. I greeted the guests and started the program by read-aloud 江雪 (River Snow), the first of three selected classical Chinese poems on the theme of winter for the evening. River Snow is a pentasyllabic quatrain by Liu Zongyuan (柳宗元), a Tang Dynasty(618 - 907) poet whose interest in Buddhism was pretty obvious in this 20-character poem about a lone old fisherman fishing in the middle of the icy river on a snow day. After reading the poem in Chinese, I turned to the calligrapher, whose writing was projected on three big screens so people could see from every angle, asking her to write the character “寒“ (cold) in three calligraphy styles: the regular, the seal and the running style, all of which were established during Eastern Han Dynasty (25 - 220 A.D.) The regular style is most commonly used today; the seal style, while is completely archaic and only appears in calligraphy as an art today, is quite useful in deciphering the roots of Chinese characters. Known as pictographic, Chinese characters often keep more meaningful parts in the seal style that lead to better understanding the etymology of the character. For example, 寒 in seal style shows a curved roof on the top, with layers of straw underneath and a man in profile curled up in between. At the bottom of the straw, two sharp lines further indicate the frozen water, another sign for coldness. After the explanation of the etymology of 寒,the calligrapher continued with writing the poem River Snow in its entirety, while the musicians joined by playing Cold River and Remnants of Snow 寒江残雪, a mellow and quiet piece that connotes the poem itself.

The second poem, 问刘十九 (A Question Addressed to Liu Shijiu) continued with the winter theme but is quite different. The author, another Tang poet, Bai Juyi 白居易, known to deliberately avoid writing sophisticated poems so that they were accessible even to illiterate farmers, in this poem was capturing a moment thinking of inviting a dear friend over for a cup of newly brewed wine as the snow is approaching. The much warmer poem was accompanied by a much lighter and happier Suite of White Snow 白雪组曲. A closer look at the etymology of the character 雪 reveals that the ancient creators were thinking of snow as “solid rain” that could be swept up by a bamboo broom from the ground.

The last poem, 白梅 by a 14th Century poet Wang Mian 王冕, had a very problematic title in English, The White Mume Blossoms. Translated by the renowned Chinese translator Yuanchong Xu 许渊冲, it is only understood by very few English speakers of the word “mume”. Wikipedia refuses to explain “mume” by itself, instead says “prunus mume” is essentially “winter plums in East Asia”. I was going to take the liberty to change the title to “The White Plum Blossoms” as “plum” would be better understood. After all, who knows “mume”, which seems like a typo! However, eventually I agree with Mr. Xu and kept the original English title: plums would be a very different flower, blooming in spring and having plums as fruits, not at all the kind of winter plums in this poem, only blossoming in cold weather, white or red, never glorious with flowers nor fruits, yet with amazingly refreshing and pleasant fragrance. As they thrive during a time when all other flowers in the world are hiding from the coldness, such quality is especially appreciated in Chinese culture as it symbolizes the resilience and perseverance under uniquely challenging circumstances. For the poet Wang Mian, who’s in fact better known as a painter, the winter plum blossoms resemble him as a Han scholar/artist under the ruling of the Mongols, a non-Han nomadic group taking over China and practically the entire continent of Asia in the 13th to 14th Century. He never sought to serve in the court of the Mongols, nor the Ming court. Nevertheless, the poem reading was met with a classical piece, Searching Plum Blossoms in Snow 踏雪寻梅, which in the end turned into Jingle Bell, played on Pipa accompanied by flute.

The guests were given the choice of following the calligrapher to write in brush themselves, or just sitting back and enjoying themselves. Wine and tea were carefully served outside of the room. People had to get up with their masks on to fetch the drinks themselves. It would be too hard to imagine a dry literati salon.

It seemed everyone had a really good time, including the musicians, the calligrapher, my colleagues and myself, and of course, the guests. I didn’t hear anyone tested positive with covid afterwards. But I did get in line for 3 and half hours myself to get tested the following Sunday. It was negative.

It certainly would be the last in-person program for a while.

Appendix:

China Institute Literati Salon: Along the Hudson River

The Program

6 :00 – 6: 30 pm

FLOATING STATIONS: Pipa, calligraphy and classical poems

no drinks please; masks on all time

6: 30 – 7: 15 pm

INTERACTIVE IMMERSIVE PROGRAM

Session I

Poetry Read-aloud: River Snow 江雪

Music: Cold River and Remnants of Snow 寒江残雪

Calligraphy: 寒

Session II

Poetry Read-aloud: A Question to Liu Shijiu 问刘十九

Music: A Suite of White Snow 白雪组曲

Calligraphy: 雪

Session III

Poetry Read-aloud: The White Mume Blossom 白梅

Music: Searching Plum Blossoms in Snow 踏雪寻梅

Calligraphy: 梅

7: 15 – 7: 30 pm

Q & A; Free exploration

Music performance: Yi Zhou(周懿), Yiming Miao (缪宜民), Rex Benincasa

Calligraphy: Weini Zhao (赵娓妮)

Poetry read-aloud: Shenzhan Liao (廖申展)

Three Poems: